CW: suicide, systemic trauma

It’s been 3 years since my last brush with suicide. I’m grateful that I had the support to choose myself in that moment because the growth has been amazing. So much so that that wasn’t my first time with suicidal ideations, it set me on a path to ensure it might be my last. That’s remarkable considering all the stress we’ve been through with the pandemic, with all the wild policy and social changes that defy precedent or reason. I have struggled, but it hasn’t gotten nearly as bad because I had to make the difficult choice to love myself. It took me giving up on my “important work” as a disability attorney and department director for a nonprofit in order to finally get right with myself again.

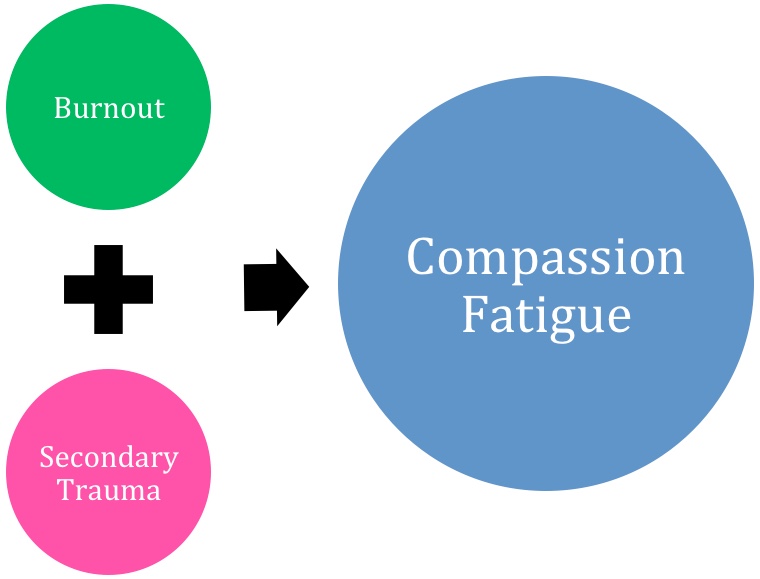

Think about that for a moment. I had to give up the meaningful, problem-solving work of removing barriers for folks who were unhoused, disabled, and overwhelmed with trauma in order to have enough room to process how the work was recreating my trauma and slowly killing me. Friends, I’m not the only one who is in this boat. Our work is so steeped in vicarious trauma that any of us who have trauma in our backgrounds (per the National Council of Behavioral Health that’s at least 70% of us) could be dealing with active re-traumatization of our own issues just by serving others.

The irony is that our own wounds are what makes us so good at this work. We are Wounded Healers (another post for another day). We care so damn much because we already know what it feels like to be traumatized, frozen, frightened, and uncertain of a scary future. This is an inherent risk of the work…as is the cyclical nature of how burnout decreases institutional wisdom. We end up recreating the very needs we are here to solve. In my opinion, at least in helping professions, this is an exceptional reason “why people don’t want to work anymore”.

The very systems designed to assist people with rebuilding resilience were draining me of mine to a near-fatal degree. Three years ago, before COVID would start to spread in China, I made an impossible choice to set aside my nonprofit do-gooder work in order to regain my strength and resilience. I had no other choice but to walk away and choose myself. Since then, nearly everyone I worked with three years ago has moved on to something else, driven out of this work not out of any personal weakness, but because of systemic trauma.

Looking back at my Survivor’s Day: August 22, 2019

I took this selfie in the morning, like many other mornings to greet friends on Snapchat and Instagram. I went to my senior manager meeting at 8:30 am and updated our boss on my department’s achievements, proudly marking off a major goal. I walked back to my desk feeling like the day might finally go my way. But when I opened my email I was met with more problems and worries, each one enough to monopolize a full day on its own. The stakes felt too high, everything a priority all at once and I didn’t realize I had all the symptoms of undiagnosed ADHD comingling with my trauma. When I arrived that day I had no idea that by 11 am I’d be in my car two blocks away on a last-ditch call with my therapist who was debating putting me on a suicide hold.

I’m glad she didn’t. My professional experience showed me that hospitalization wasn’t always the right answer. The trauma could be infinitely compounded, solidifying distrust in the same systems that were failing my clients, which was why I was suicidal in the first place. Placing me inside this everlasting loop of inadequate responses to human suffering wouldn’t have been supportive. We both knew how this could play out – and that hospitalization might trigger consequences with attorney regulation too. I’m grateful my therapist understood the intricate interplay of how unaddressed systemic trauma wasn’t be solved by more systemic trauma. I’m grateful she knew me well enough to see how I might use those consequences to further punish myself. We compromised, created a safety plan, and I stuck to it.

The source of my suicidality was that I couldn’t compartmentalize the pain of the people I served like others told me to. Common practice in the mental health industry was for people to be treated as “cases that need to be managed”, which also contributed to the ongoing trauma of my clients. My sickness came from navigating the dangerous waters of inaccessible human services “solutions” that kept people locked in poverty.

The entire time I worked in the counties I was greeted everyday with reminders of the worst years of my life when I was outed, unemployed, and too depressed to function. Our experience had been so frustrating – we submitted verifications over and over again only for the scanning room to always lose the copies. My kid was off his meds for four months because of this administrative issue. Fast forward to a few years later and I’m dealing with clients and staff who are having the exact same issue – the scanning room habitually losing paperwork, which then shuts off or denies benefits. Proving to me that even when people are doing the best they can, the system can still traumatize through its gross incompetence.

It wasn’t that I didn’t want to work, it was that someday I wanted the solutions I was applying to stop the bleeding wound of poverty. My depression wasn’t just because of my trauma, but it was related to how my own wounds were activated by the trauma embedded in these processes. And I know I’m not the only do-gooder out there who is feeling this, right?

Do-gooders bear the weight of society’s indifference

I went through trauma twice – the vicarious trauma of my clients as well as the retraumatization of my own issues. That put me into survival mode all the time, oscillating from one trauma response to the next. I masked it the best I could because I loved the people and causes I worked with. And I especially loved my clients. I was the leader of the ride-or-die do-gooder club.

But sorta like the first rule of Fight Club is “we don’t talk about Fight Club”, the first rule of do-gooders club is we privately spill all the pain and trauma we feel in our workplaces to each other, but in public with our bosses, clients, and especially funders, we’re happy little worker bees. We buzz around delivering aid to the needy satisfied with surviving on sweat equity, pizza parties, and kudos. We don’t make waves because if we do, we know it will be our clients and co-workers who suffer.

Does this sound familiar? Are you a do-gooder too? You might be a do-gooder if you resonate with any of the following statements:

- You truly meant it when we wrote: “I want to save the world” for our college essay and we haven’t stopped pursuing that goal.

- You work in a helping profession or a public service capacity of some kind including government, social work, law, medical, mental health, advocacy, nonprofit, food cooperatives, spiritual healing, education, or public policy.

- You have a passion for social justice (and can discern when someone is performative or disruptive for no good purpose)

- You are empathetic and open-hearted and just feel so much. You imbue that in any work you do even if it doesn’t directly help the communities you care about.

- You believe in the power of de-escalating conflict, advocating for diversity and inclusion, communicating with compassion, and meeting people where they are.

- You see patterns in the larger world and you know something needs to be done, but might not have the individual or organizational power to leverage the systemic solutions and buy-in that is needed for progress to begin.

- You are a resister who felt like the wind got knocked out of you by Trump’s victory in 2016 and notice that America isn’t so great right now as a result.

Friends, you’re not alone in this. Too many of us have felt that gnawing dread, the perverse realization that no matter how many hours we put in, no matter how passionate of a team we have, and no matter how much knowledge, persuasion, and gumption we put into our work this will never be an adequate substitute for the holistic transformation of all of these systems. The interconnectedness of health, justice, employment, and even the environment is too great for us to ignore how trauma flows through all of them. These systems are so intertwined with each other that problems or adverse outcomes in one could completely derail others which only increases the suffering we absorb from clients and experience on our own.

We talk a lot in helping professions about accountability, but we rarely place a spotlight on the baked-in inequities of these administrative functions. Additionally, the general mood of skepticism in the American workforce has awoken several in the helping professions to the disproportionate weight of need they’ve carried on their backs during their careers. Do-gooders have stopped suffering in silence and we see how deep and intricate the problems really are. Not to mention that none of us got out of this pandemic without loss. We can’t even begin to comprehend the collective waves of grief that will come once we recognize the true impact years from now. We can never clearly enough when we’re in the thick of it.

Yet that’s what we’re expecting of people in helping professions all the time – to somehow fix the big picture when we’re busy putting out individual fires while we too are on fire. A client dies waiting for services and we’re expected to carry on. So instead of dealing with it directly on an agency level, we absorb it only to spend several sleepless nights obsessing about the what-if questions that can kill the soul of a do-gooder: What if I had pushed harder? What if I had escalated it? What if our system actually gave a damn about anyone? What if this is all hopeless?

And what’s most unfair is that the burden of our optimism ends up landing on the people we serve. We are so on edge, holding the stories of an overwhelming caseload together that the behavior of one client, one outburst or argument, can make or break our day for the rest of our clients. And their heart-breaking generosity which they can’t afford is the unfairly thin thread we weave our hopes on. We start this work thinking If I can help just one person this will all be worth it. But we wind up thinking, How can I possibly make a difference when the need is so great and I am just…me?

Once I got into management I at least had the freedom to be choosy about who I hired. Too many people even in our professions think that our clients show up because we give them handouts and swag, participation trophies, and free lunches. And while that might have been what first got them through the door, it was the way we treated our clients as human beings that made them stay. We created a safe, accepting environment where they could loosen some of their emotional armor to breathe and be real with us. And THAT is what really makes do-gooders special.

Success for our world won’t come from “saving everyone” but rather, using our power to give people room to kindle their fires again, first to survive these systems, then to dismantle and rebuild them into something better. For once you stop suffocating someone with trauma, once they feel the safety of transparency, the support of acceptance, a courageous little seed of trust now has some room, light, and nourishment to grow. Impossibly, they cultivate a faint hope that they’re worthy.

It is then, and only then, that resilience begins to grow. This is the kind of success that we do-gooders can never objectively measure, but we all intuitively know when we see it. I think if we listened to the do-gooders, we might actually solve some problems and take us out of this never-ending loop stagnating humanity’s potential.

A systemic cold war on do-Gooders

What is the end goal of a do-gooder? To put themselves out of a job. To have solved world hunger so they never have to beg for grocery stores to supply leftover food again. To have solved illiteracy so all they have to do is maintain the supply of books and trainings throughout a given year. To have solved homelessness so they never have to worry about clients dying of hypothermia on a cold winter night again. The ultimate end game for a do-gooder is to keep doing good until there is no more good left to do (or is that just me)?

It’s when we keep doing good and the problems keep getting worse, that resilience becomes impossible to sustain alone.

Capitalism is exceptional at romanticizing the work that we do. I could make obscene amounts of money selling my shock and awe tales from within the trenches at corporate diversity conferences. But that’s because the willpower to do anything about the policies that cause the problems is not absent, just…dormant, always subject more to an obligation to make shareholders money than becoming do-gooders themselves. At best we are inspiration porn for the next corporate giving day. Even the recent donation by the owner of Patagonia wasn’t just altruistic, it was a business decision to consolidate decision-making within his family while giving the company significant tax breaks. None of that is to knock private philanthropy, because the grants are generous and appreciated, but it pales in comparison to the impact they could have immediately if these same groups used their influence to just change their policies, raise salaries, and have more of an impact on environmental justice.

The healthiest philanthropic relationships are those where funders listen to the do-gooders, bringing us together to share our challenges, strategize alternatives, and problem-solve issues. They collaborate with us becasue they genuinely want to solve the problems, figure out and fund true solutions. The best philanthropists are those who have identified a problem and pay the best minds and biggest hearts to solve it – because it takes both. They know that our humanity is interconnected and their funding priorities align with that vision.

Unfortunately, that’s not always what we experience. Too often it’s a one-sided relationship or dependence. We offer our best ideas and gratitude but when that funder’s priorities change on the next grant cycle, the resulting chaos could upend all of that hard work, sabotaging programs, clients or even the basic ability to feed ourselves into a toxic whirlwind of stress and trauma. And I have learned that sometimes the most effective executive directors in the current climate aren’t those who are leading policy or making the best decisions for staff and clients, but those who have a good enough relationship with funders to be one step ahead of the game, having new funding lined up to continue programs without interruption.

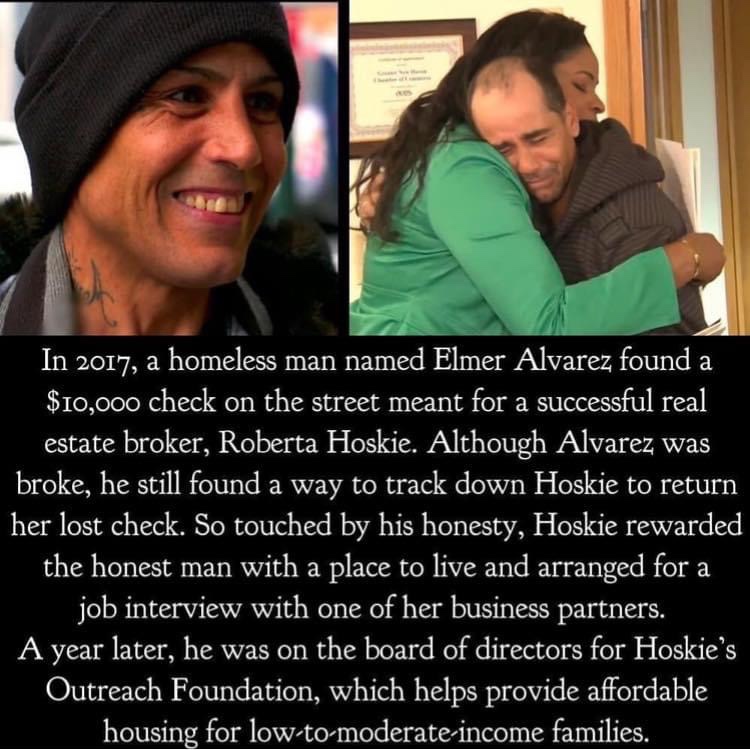

The world loves to celebrate goodness, but it believes it should be infinitely self-sustaining without its help. It will applaud someone who goes out of their way to help another but doesn’t meaningfully invest in replicating those results. Nor does society interrogate how their own treatment of these collective problems as an issue of individual willpower is actually taking us further away from the true long-term solutions.

Clients shower us with titles like “angel” or “miracle worker” all because we were the first ones in a very long line of people to treat them as a human being instead of cases to be managed, numbers to be reported at the end of the month. They have too often been subject to an oppressive world that keeps reminding them that they are losers for living in poverty, so even a small software glitch can feel like the end of the world. Any setback douses that tentative spark of hope. It’s hard not to feel like we’re stuck in a systemic war against goodness as a whole, death by a thousand paper-pushing, bootstrapping, micro-aggressive cuts.

Interconnected problems require interconnected solutions

Take for example a very common problem that I’d see in my disability cases: racism, ableism, or transphobia in a health care setting that could leave that client without the care or documentation they need for disability benefits. If denied they are more likely to experience homelessness, decompensation, or even death. No matter how much I believe in clients’ cases, no matter how hard they work to access care, all it takes is one doctor whose casual racism is tolerated by staff and superiors to upset this delicate board of survival-level dominoes for a whole family. Not to mention the collection of micro-aggressive moments like that negligently stir up the traumatic memories of clients, which might get taken out on literally anyone the rest of the day.

Likewise, some of these systems take the functionality of others for granted. Another example: I had to fix a case where a disability judge assumed the fact that someone has TANF at all is evidence per se that they can work because they “successfully navigated a works program”. But the judge fundamentally misunderstood the rules of the program and didn’t ask the right questions about her time on the program, which actually wasn’t “successful” at all. So the failure of those systems to interact cooperatively to understand how they each function means my client not only gets denied disability but would then have to meet the work hours requirements or lose TANF unless she can find an attorney willing to take her appeal a step higher – which is costly. But these systems are dying under the weight of their own rules and meaningful changes to policy are rare.

These anxiety-ridden, trauma-laden roadblocks trip up even the most competent people, much less those whose executive functioning is consumed with only one question: How can I keep myself safe in this unsafe moment? When we look at the interconnected impacts of trauma and toxic stress on health care, employment, mental health systems, housing, finance, and education, we cannot begin to comprehend the impact that we have on one another, specifically from this systemic viewpoint.

Last week was Orange Shirt Day, a Day of Truth & Reconciliation for indigenous residential school survivors and victims. I think we have barely begun to scratch the surface of communal suffering that has come from this one set of policies alone. The trauma was baked in, perpetuated on not just the survivors, but the families they left behind, the community roles that went unserved by these children or their grieving parents and siblings. The cost of that trauma is staggering.

Research tells us that the impacts of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are significant to both the individual and society as a whole. In short, the suffering of children doesn’t end in childhood, they become adults who continue to suffer. They have trouble concentrating, are distrustful of themselves and others, are more likely to contract sexually transmitted infections, have pregnancy complications and have a higher likelihood of chronic health problems like diabetes and heart disease. According to the CDC, the estimated annual economic burden of ACEs alone – just child maltreatment is more than $400 billion. Even a 10% reduction in ACE’s could save us $56 billion a year.

Likewise, how much of an individual’s spending power is spent as a result of untreated symptoms of PTSD, schizophrenia, fibromyalgia, ADHD or a TBI just to name a few? Any of these conditions can impact memory, concentration, persistence, and pace. How much does a lack of money negligently exacerbate or trigger trauma responses?

But this isn’t confined to government or nonprofits. Ableism is presumed in our financial policies by taking for granted that everyone is neurotypical. But they aren’t. Many have undiagnosed autism, ADHD, untreated TBIs or PTSD, all of which impact executive functioning and might need additional supports.

We talk a lot in my house about how rich we might be if we didn’t always pay the ADHD Tax for my poor processing memory. A medical company recently took me to collections over a $5 bill that got buried in one of my many doom piles that got moved by someone else. It was the only notice I received and while I absolutely accept that it was my responsibility to pay, the amount of work it takes for me to organize myself to do it is made even more difficult by how my brain works – costing us both more money that didn’t need to be spent.

Yet, that company made a policy choice to spend all that money to send me to collections for a $5 bill. In the alternative, they could have just sent a second notice, had someone look at the account and give me a call, or even sent a text with a link for me to pay like other companies have learned to do. Thanks to our societal prioritization of profit over people though, I’ll have a lower credit score to teach me my lesson in “fiscal responsibility” like I’m 6 years old because of wasteful policies that disproportionately impact poor and disabled folks. And having less money definitely won’t give me panic attacks, right?

Our public policy priorities often dismiss these as “excuses” as in “You’re just making excuses for being lazy”. Sure, we could see it that way, or we could see it as an accidental war on the people who already are facing barriers, poverty and a revolving door of trauma. Wonks throw it in a file labeled “anecdotal” or “testimonial” but never really circle back to connect the dots between the deeper data and lived experience.

Whenever policies hurt vulnerable people it also signals a silent cold war against the do-gooders who have to problem solve these compounding crises. We don’t get extra pay or time off for navigating these messes or intervening in the suicidal ideation that comes from these setbacks. We just have to…absorb it all and hope someday everyone else fixes their terrible policy choices. The best we can do sometimes is simply endure and hold space.

Instead of scrutinizing our clients for their financial choices, perhaps it’s time our society makes better financial choices too? Because our willful ignorance of the cost of trauma is what is more fiscally irresponsible than whether someone uses their food stamps to buy Cheetos. It seems perfectly clear to me that the absolute best investment we could make as a society is to stop traumatizing people collectively through public policy, or at least make our policies more trauma informed, collaborative, and transparent.

We are ignoring the impact of trauma on our society to our own detriment. Why? Personally I think it’s because cold rationality is easier than warm compassion. To contemplate being trauma informed in policy means those policy makers, advisors and constituents will also have to confront their own trauma to recognize the need. And considering how much of the world seems to be fine with negligently or even deliberately inflicting trauma, it is up to those on the ground, the helpers suffering from compassion fatigue, to encounter humanity on its worst day and make a difference.

So at the very least, we need to help the helpers. We aren’t holding up a safety net, but travesing a trecherous spider’s web trapping us, sucking us dry, leaving us isolated, hopeless, burned out and resentful. No matter how optistimistic we do-gooders are the cruel disinterest in the hearts of our leaders, the dehumanization in their talking points leaves us feeling hollow.

Therapy and personal boundaries alone can’t fix these problems… but a heart-centered approach to public policy can.

[…] few weeks ago I posted about my own experiences of lack and how they informed both my work as a disbility attorney, but also my experience of burnout. It […]